The Trillion Dollar Cost of Ignorance

Tech journalist Robert N. Charette closed his recent comprehensive critique of IT failures with a blistering quote pulled from Cicero some 2,000 years ago:

“Anyone can make a mistake, but only an idiot persists in his error.”

Charette, who has been chronicling the cost of software failures for two decades, originally published his story in IEEE Spectrum under the savage title “The Trillion Dollar Cost of IT’s Willful Ignorance.” The story has subsequently appeared in the digital edition under the more gracious headline “How IT Managers Fail Software Projects.”

I think I prefer the original title.

To be clear, I’m an enthusiastic consumer of medical studies showing that optimism and “positive effect” (e.g. ‘looking on the bright side’) will help me live longer. Strictly speaking, depression does not bode well for my life expectancy.

The weight of Charette’s Cicero quote and the preceding expose on the many systemic failures that continue to plague the IT world may well have taken time off my life.

The tragic TL;DR is that we don’t learn enough from our past mistakes.

Especially alarming is a telling reference to the Consortium for Information and Software Quality (CISQ) report showing the cost of operational software failures in the US in 2022 was $1.81 trillion – larger than the US defense budget for that year. The author goes on to posit that far from being a digital deus ex machina, AI will only make these problems worse.

Further endangering my health via sad news, yet another article published in IEEE Spectrum late last year – Stephen Cass’ “The Biggest Cause of Medical Device Recalls” -- concludes that of the 5,600 software-driven medical device recalls analyzed by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), 84% were due to ‘software design’ and 2% were due to cybersecurity.

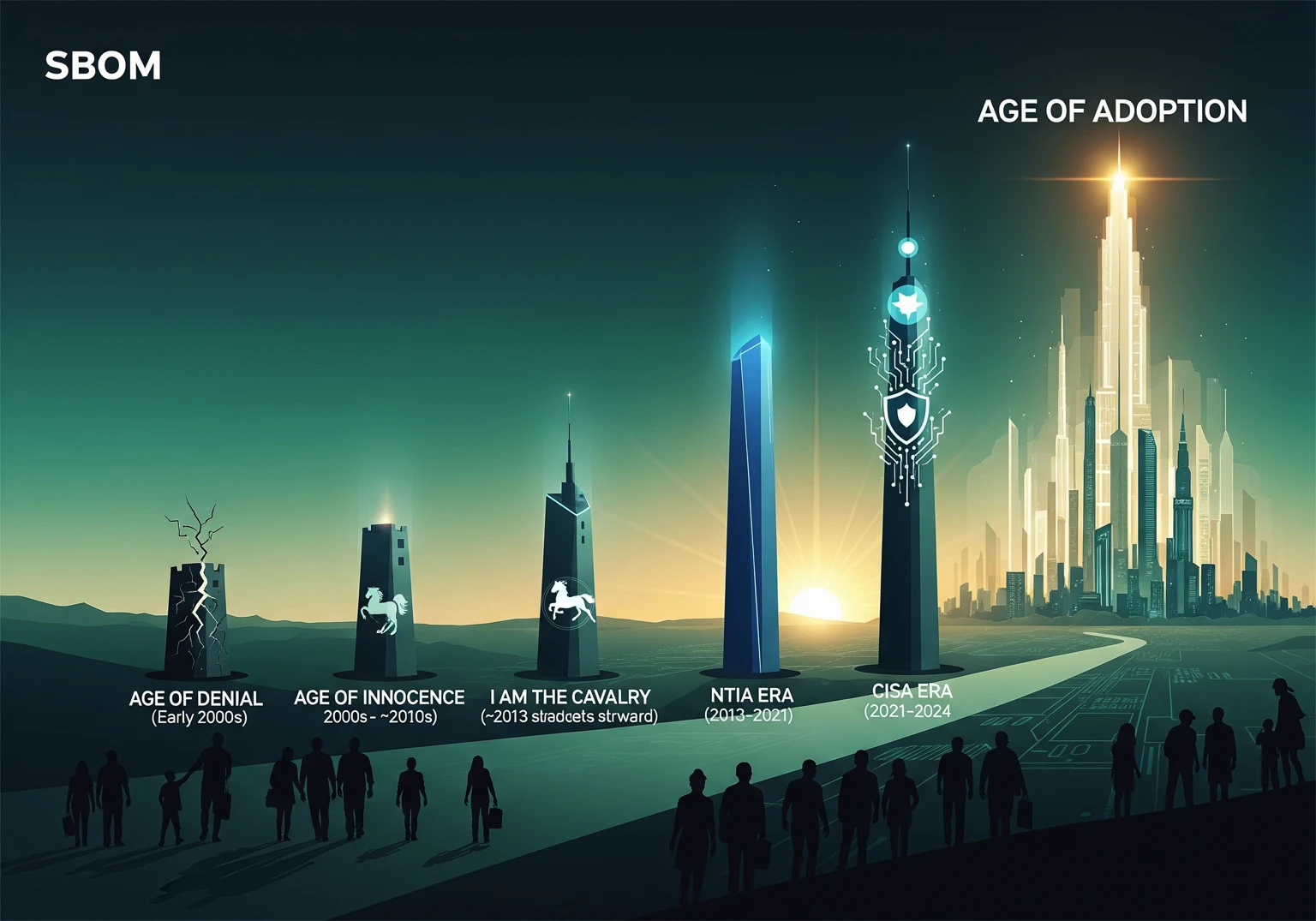

My world is cybersecurity. Specifically, I’m a dogged advocate for SBOM adoption. You might recall my post from August – “Dawn of a New Era”—in which I celebrated entering my sixth SBOM era – the era of adoption.

What exactly do these two IEEE Spectrum stories have to do with SBOM? At surface, not much. Neither story mentions SBOM. And SBOMs won’t be the be-all-end-all silver bullet. Without explicitly invoking my favorite tool for cybersecurity automation, both articles hint at a need for a larger paradigm shift, one in which the SBOM mentality figures prominently.

Both Charette and Cass rightfully fixate on the chasm between software development and real world integrity. This is the space we occupy. At a fundamental level, SBOMs are system awareness tools, bridging the gap between creation and credibility.

The unexpected benefits of the “design use case” is one of my major takeaways from a career spent both using SBOMs in software development teams I have led and guiding consulting clients through the implementation of SBOMs. SBOMs get a lot of great ink for their cybersecurity and licensing benefits, but IMHO they don’t get enough credit for their use in component selection during software design.

Charette points to the “inability to handle the project’s complexity” as a major cause of software project failure and warns that “the more complex and interconnected the system, the more opportunities for errors and exploitation.” A good SBOM doubles as a key to understanding the software system it serves. Assessing product from an SBOM perspective offers unique insights crucial to reducing redundancy, cruft, and inefficient design.

Since the early days of the NTIA work, I have been an advocate, usually the sole advocate, of using SBOMs during software design. A developer is more likely to use an existing library rather than adding yet another copy because, with the SBOM, they can see what is already there. SBOMs also help with the Hawthorne effect. I began my career at AT&T’s Bell Laboratories, so I am particularly enamored of this as it was a Bell Labs study that discovered it. The fact is, we work harder and do better when we know someone may look at our work. Knowing others can observe their SBOM, developers likely will put a little extra effort into ‘cleaner’ designs. Developers will also more likely to look at it’s OpenSSF scorecard and see flags like it has a single maintainer. They won’t add a package with 23 functions just to use one of them. Instead, they’ll find the functionality they need in a different ‘cleaner’ package that has ‘just what they need’. For example, Heartbleed cost the economy on the order of $500M. Most, if not all, of the affected systems did not even use the OpenSSL extension component that left them open to compromise.

Many may (and do) disagree with me on the practicality of using SBOMs during design, but I assert that not having an SBOM is equivalent to admitting that you can’t understand the complexity of your system and that your developers are comfortable increasing your chance of failure, not just with regards to security, but also basic functionality. You need look no further than the FDA’s numbers comparing the cost of deficient design (84% of software-related recalls) against cybersecurity vulnerabilities (2% of software-related recalls).

Repeating myself – SBOMs won’t be the be-all-end-all silver bullet for design errors. But I think a reasonable expectation is actively using SBOMs (for licensing, security, and design) could keep just one project from failing out of every hundred failed projects. In an industry plagued by 1.81 trillion dollars of IT recall costs, that’s over $18 billion in savings.

Gloomy as the figures may be, I’m heartened to think that the sixth era of SBOM has our community poised to learn from costly mistakes. Maybe we can all avoid being Cicero’s idiots.

.svg)

See Cybeats Security Platform in Action Today

We shortened our vulnerability review timeframe from a day to under an hour. It is our go-to tool and we now know where to focus our limited security resources next.

.svg)

SBOM Studio saves us approximately 500 hours per project on vulnerability analysis and prioritization for open-source projects.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)